The debate about the future of education is perhaps all too familiar for us.

We debate about the means of evaluation, the mindset of students, and the creation of alternatives. Never escaping the conversation on the future of education is this word: system.

On the one hand, there are the strategies introduced to revamp the ‘system’ to meet the demands of a ‘VUCA’ (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) environment. This includes discretionary admission to secondary schools, the ‘teach less, learn more’ approach, and now SkillsFuture, among others.

On the other hand, disagreements with assessment methods, and anxieties about slipping down the standards against which the ‘system’ values (or devalues) us more than abound in everyday banter.

Qualms about the ‘system’ dominated, too, at the Ministerial Dialogue with Acting Minister for Education (Higher Education) Ong Ye Kung, organised by the NUS Political Science Society earlier last month. Many students came forth and asked about the truth of meritocracy, biases based on one’s major, as well as the relevance of the Integrated Programme – essentially probing the efficacy of past changes.

These questions were significant in speaking volumes of the way something more fundamental has remained unchanged – the obsession with the need to stay afloat within the ‘system’. It is an obsession more broadly interpreted as an incessant worry about one’s position in this system, and as compared to everyone else. And in this system, we will always be categorically judged against a single set of standards. That is, whatever it means, or does not mean, to us, grades exist.

Amidst changes to transform ideals of academic success, and reconfigure perceptions of these standards in the system, are we uncertain, or even confused, as to where we belong? How exactly are we to understand grades?

A friend once told me, “I do not like this professor, I went for consultation, and wrote my essay as he told me to, but I did not get an A for that essay.”

Perhaps for some, grades are the be-all and end-all of university and a perfect CAP is all academic success means. That is respectable, no less, because it takes grit and commitment to achieve.

And then there are those who could confidently profess a purpose in an education beyond, and the satisfaction of which outweighs the burden of less-than-perfect grades.

Or, how many of us probably fall somewhere in-between? How many of us find within ourselves passion for more pursuits, but often find ourselves restrained because of ‘studies’? We find a lot of purpose in what we do, or what else we could do, beyond our core modules and major curriculum. Yet, by habit, conditioning, or otherwise, we fall in line along the rat race for grades.

Speaking at the inaugural St Gallen Symposium Singapore Forum, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Chan Chun Sing warns against us becoming a ‘yardstick society‘: “This is something I fear for our society – where everyone goes after the same thing, the same yardstick, and we end up in what sociologists call a ‘prisoner’s dilemma’. That’s what scares me.”

I doubt we all subscribe to the same yardstick, because it seems that many of us know that a lot more than grades do matter, and we could be a lot more than grades. We are perhaps fuller in terms of our ‘idealism quotient‘, quite unlike the way Professor Mahbubani laments it is lacking in us. Though, it seems that we do abide by this same yardstick and seek to excel in its terms because we feel compelled to do so. What is the alternative? The only way to graduate is to hold out in terms of our grades.

Even if we take a quick look at Tembusu, there is so much passion among students to do something, to want to step up, to search for and share knowledge – think of conservation projects under the Rector’s Shield Initiative, Student’s Teas, Tembusu Pundits, Zeitgeist, and so much more. There is, however, also so much hesitation because there is always that nagging responsibility of “need to study leh”.

What scares me, hence, is that many of us will lose many other things that mean so much to us, because the standards to which this so-called system holds us against are simply inescapable.

In his first public speech on Higher Education as an Acting Minister, earlier last year, Mr Ong iterated the need of “rethinking of the meaning of higher education”.

“Every Singaporean counts, and he or she can only count if the system allows maximum play of what he or she can do and is best at doing.”

I feel that aside from making amendments to this ‘system’ upon which blame is piled and where effort for change is concentrated, would it be that what we need is assurance and clarity? That is, being able to know and believe that it is alright to be a lot more apart from our grades, and it is alright to feel contented and confident because of what we have apart from our grades – whether or not our grades are in the best shape.

This is not only a question of how we could reconcile our understanding of a well-purposed education within this ‘system’, but also an issue of being comfortable with and in confidence of our own notion of a well-spent life in an environment that may be defined by a different set of expectations.

So, dear you, I wonder what your clarity and your calm is.

In a university education, what matters?

What should matter, really?

–

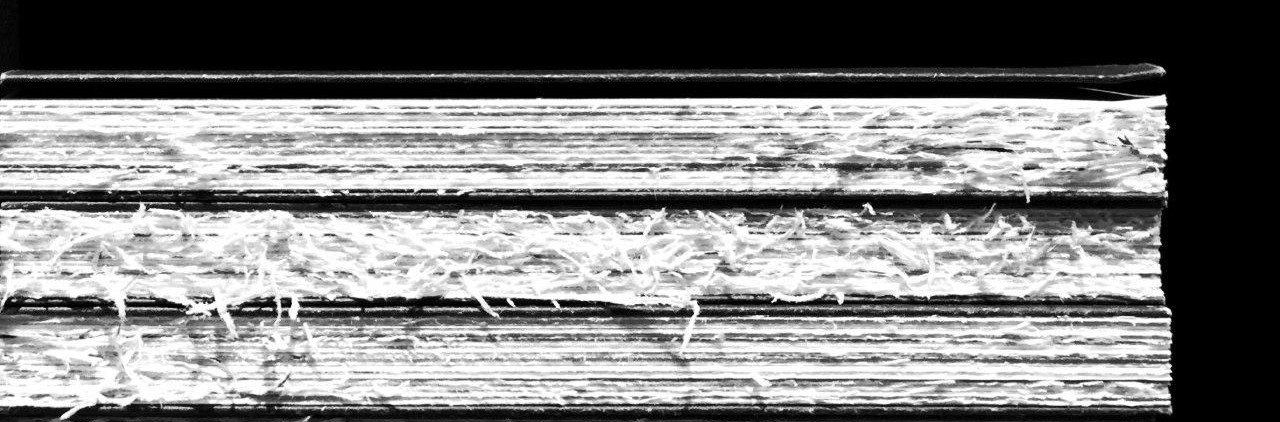

All images by Jesslene Lee.

About the Author

Mad for adventure and stories, Jesslene often walks down unmarked streets and talks up wild strangers. Leading quite a monochromatic, unplugged life, she also loves wandering about.

Leave a Reply