“I don’t have two lives. This is one life, and the personal pictures and the assignment work are all part of it.”

– Annie Leibovitz, A Photographer’s Life, 1990-2005

On October 2006, Annie Leibovitz published a series of photographs taken over the course of her 15 years as a professional photographer, entitled “A Photographer’s Life 1990-2005”. In this exhibition, the general public would recognize instantly her professional, commercialized photographs taken for magazines such as Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone, most notably a nude and pregnant Demi Moore, or a nude John Lennon curled up against a fully dressed, somber Yoko Ono. At the heart of this work, and also what drew the most criticism at that time, was the interspersing of personal elements amongst the professional; by blending in previously unearthed personal photographs of Leibovitz, her family and Susan Sontag.

(Untitled), n.d.

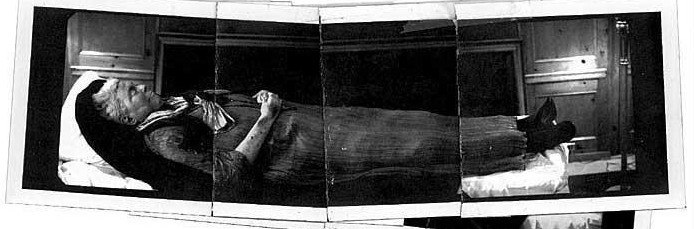

A particular work from this collection that I would like to draw focus to is the untitled photograph of the corpse of Susan Sontag (above), laid out in its post-mortem, funerary state (Fig. 1). Printed on gelatin silver print, in black and white, the very subtle contrast (or lack thereof) of the white bed against the plethora of greys and black that the background and Sontag is swathed in, serves to bring out the somber tone of the subject matter. Another key feature of this photograph is how it is split into several parts overlapping each other and stitched together with sticky tape, suggesting a kind of “physical deconstruction” of Susan Sontag through Leibovitz’s eyes, while the curved formation of the newly reconstructed photograph, removes, ironically, a certain stiffness in death that the otherwise normal landscape photograph might have portrayed. Similarities of her lifeless body can be drawn to an effigy, and when transcribed through the medium of photography, can be alluded to perhaps, her undying image in the various fields of intellectualism she was involved in. Lastly, this somewhat voyeuristic work also presents a nearly unrecognizable figure of this larger-than-life public intellectual that had nearly reached celebrity status at the time of her death. As a result, many have criticized the ethics of Leibovitz in publishing publicly something which would conventionally be accorded greater privacy, one which Sontag herself is unable to have a say in. In particular, Sontag’s son David Reiff, labeled the photograph as “carnival images of celebrity death”. This was part of a larger polemic that condemned her photographs of Sontag as unethical. I will be expounding upon this in greater analysis through the essay.

A Photographer’s Life 1990-2005 – Exploring Leibovitz’s Oeuvre

As this work belongs to the wider oeuvre in Leibovitz’s collection “a Photographer’s Life 1990-2005”, reference will be drawn from the photograph I have chosen to other pieces in her collection. The organization of her collection as a whole suggests a form of storytelling, and like any story, Leibovitz begins with an introduction in writing. Here, she explains her photography and sets the context for the juxtaposition and sifting between intimate photographs and professional portraits in her exhibition. The first work following the introduction, that catches the audiences’ eye, is a picture of Susan Sontag at Petra, Jordan (1994) (Fig. 2). Also printed on gelatin silver print, this black and white photograph captures the contrast between light and dark again, through its black and white medium, with the shadowy figure of Sontag being drawn into focus against the narrow white backdrop, and the immensity of the dark, towering rocks around her. In contrast to the photograph of Sontag’s death however, the background does not create a sense of dimmed solemnity, rather, the anthropomorphic curves of the rock surrounding Sontag seem to give her a larger-than-life presence, while drawing the audience’s eye to her actual smaller and shadowy figure at the foot of the rocks.

Susan Sontag, Petra, Jordan

1994

71.3 x 58.6 x 3.2 cm

by Annie Leibovitz

While this highly personal photograph, that draws immediate focus towards Sontag as the centerpiece, might be enough for the discerning eye to realize the level of familiarity Leibovitz and Sontag shared, it is still difficult to accurately pinpoint the exact nature of their relationship. However, as the “story unfolds” through the exhibition, the depth of intimacy between photographer and subject is continuously explored and developed. Perhaps the epitome of this can be found in a picture, entitled “Susan at the house on Hedges Lane, Wainscott, Long Island (1988)” (Fig. 4). It is important to note that while this picture was taken a good six years before the one at Petra, Jordan, Leibovitz’s re-ordering of the pictures in the development of the exhibition is ostensibly intentional and further reinforces the notion of storytelling.

In this photograph, instead of the “solitary and intriguing figure, a sort of prowling lioness with…the penetrating gaze of a woman who did not suffer fools gladly”, the audience gets a glimpse into a rarely seen side of this famous intellectual force. Lying on a sofa with her legs propped up on one end and her hair almost flowing off the edge; the languid, almost faint Sontag, exudes the tired, the familiar and the ordinary. It is a posture taken, not uncommon to the rest of us. Yet, put into context, the thematic light, an idiosyncratic feature of Leibovitz’s photographs, filtered in from the window seems to illuminate Sontag beautifully, overcasting the weariness that Sontag presents, and in fact, seems to place her in a state of peace and restfulness. It is a simple picture. Set against the larger backdrop of Sontag’s life however, it is this minimalism illustrated as well as the peace manifested in the moment captured that distinguishes this photograph. By this time, Sontag would have fought cancer once in the 1970s, and this would precede two more relapses, one in the 1990s and the last one in 2004, culminating in her death. Her life as female American public intellectual was not without its tribulations as well, struggling with poverty in the 1960s and her highly opinionated and sometimes opprobrious writings were met with criticism and controversy.

Parallels can also be drawn between Sontag’s languishing figure and the commercialized photographs of models and celebrities also found in Leibovitz’s collection. For example, a photograph of Karen Finley at her home in Nyack, New York (1992) (Fig. 3) features a naked Karen Finley, wearing only socks with her bare back towards the camera, but languid and lying across a sofa, in a similar fashion. The backdrop is nearly identical – a side table with books, and a heater unit. Prima facie, the photograph of Sontag fits perfectly into the oeuvre of celebrity assignments that Leibovitz took, Sontag herself a celebrity by her own right (this drawing itself back to the discourse of the ethics behind publishing “celebrity images” of Sontag). Upon closer analysis, the photograph of Sontag cannot be taken as a mere assignment. The Karen Finley picture is highly idiosyncratic of Leibovitz’s celebrity works: saturated with stark colour contrasts. More often than not, this highly stylized, almost stale and overused characteristic underscores the figure-of-power at ease, and in Finley’s case, her tender, pale figure perhaps also enunciating eroticism. It is a pose that is contrived, and her unblemished bare back, the result of technological manipulation. Yet, the black and white with light medium leitmotif for Sontag works two-fold – it not only draws out her state of rest, it breathes life into the photograph and into the complete ease that Sontag, finds herself in, as subject to Leibovitz. As the other works that I shall be expounding upon exemplify, the black and white motif is significant as it strips away any visual distractions in the photograph, thereby transporting the viewer into the heart of the photograph. Here, the photograph manifests as raw emotion, reflection and metaphor. By transcribing a moment, where Sontag is at her most ordinary and partaking in something that is so intrinsic to human existence – weary but simultaneously, at rest, Leibovitz sheds light onto an aspect of Sontag the world is not privy to. In fact the hallmark of their relationship as lovers, lies in this photograph – this is Sontag seen through Leibovitz’s lens, unfiltered and in a natural state, with light cast upon her, almost lovingly.

Karen Finley at her home in Nyack, New York

1992

Frame: 99.4 x 124.8 x 3.8 cm

by Annie Leibovitz

- Fig. 4

Susan at the house on Hedges Lane, Wainscott, Long Island

1988

Frame: 58.6 x 71.4 x 3.2 cm

by Annie Leibovitz

In a way, this photograph also foreshadows the later photograph of Sontag in death. Leibovitz attempts to recreate the same lethargic grace Sontag emanates in life, by dismantling physically, the stiffness of death and assembling the image to take on a more curved and even, comfortable formation. It is the same life presented by Leibovitz in the exhibition that eventually humanizes the image of Sontag in her death for the audience. From Sontag taking a walk in Paris, or nude and weary in the bath, to her, smiling ever so slightly in a car – the pervasiveness of Sontag in such themes of everyday life is curated carefully by Leibovitz. The storyline of Sontag itself is interweaved in the exhibition with the personal story of Leibovitz and her family, charting not a plot trajectory of family/celebrity drama, but instead seamlessly fuses her personal life with Sontag into the quiet notions of ordinary American family life, love and loss. Thus, the audience is presented with Sontag as an ordinary person, unlike the intimidating public figure often shown; as a corollary, her death was not a death of a public figure, but the death of a lover, a friend and a companion.

The Leibovitz Polemics

Thus, coming back to Leibovitz’s photograph of Sontag’s death, two important key ideals are expressed here, namely death (and its relation to photography), and the relationship between subject and photographer. The former gave rise to much criticism, especially with regards to privacy and the rights Leibovitz had in publishing something that Sontag herself had no say in. This topic of ethics and the related subject of voyeurism were championed largely by Susan Sontag’s own son, David Reiff, as well as many other critics from agencies such as the New York Times. The cause of such dissent may well have stemmed from the association of death with degeneration and decay, and conversely, the emphasis placed on according dignity to the dead. It is built on a culture that privatizes grief and perhaps also betrays the prioritizing of the healthy living over death – the publicizing of something so personal and guarded would definitely have scandalized audiences. Another issue surrounding the publication of the photograph was the purported issue of Leibovitz consciously building upon Sontag’s reputation and near-celebrity status to cause scandal and publicity for her exhibition. As an inference, the candid exposure of their relationship, Sontag’s personal images and at last, her death would have been viewed as lacking in artistic qualities, and instead, as publicity modes. However, to condemn the exhibition to public scandal would be to indubitably, fail to recognize the significance death photography in relation to the general human condition. Angela McRobbie provides a more sympathetic hypothesis towards the publishing of such photographs. She writes:

“The of her unseemliness of Annie Leibovitz, one of the world’s best-known photographs, publishing intimate portraits lover Susan Sontag in the months before she died in December 2004 and then in the immediate aftermath of her death as she was laid out in the mortuary gurney, is perhaps only explicable in terms of her mourning, anger and outrage at being abandoned.”

Indeed, photography provides a platform for expression – to signify emotion and as a result, overcome oneself through such expression. Briefly, photography as a medium is important as it curates, but at the same time, creates both distance and personal sentiment towards the dead.

Yoko Araki

1990

by Nobuyoshi Araki

Photographer – Subject Relationship

Such a look into death and relationship between subject and photographer has been documented by other contemporary photographers, such as Nobuyoshi Araki. More specifically, the published “Sentimental Journey”, similar to Leibovitz’s “A Photographer’s Life 1990-2005”, features a series of black-and-whites, documenting Araki’s relationship with his deceased wife Yoko. However, while both Araki and Leibovitz draw inspiration and imply affection for their subjects by capturing ubiquitous rituals of everyday life, the manner of which intimacy itself is established through the lens differs slightly for Araki. The addition of nudity, both of Sontag and Leibovitz herself in her works, further underlines how their relationship transcended the formal boundaries of merely purported close friendship. Conversely for Araki who is well known for having sex with all his subjects before beginning his photography sessions, it is the almost lack of nudity and sex, which is idiosyncratic of his works, in “Sentimental Journey” that seems to highlight the special relationship shared between Araki and his wife. While sex is a topic that is usually associated with Araki, it is the picture of his dead wife Yoko, in her funeral casket (Fig. 5) that not only corresponds directly to Leibovitz’s photography of Sontag’s death, but also questions again the depth of photographer/subject relationships, as well as the idea of voyeurism in death photography. The ability of photography as medium to provide a platform for human response to death can be seen by comparing the emotional responses of both Leibovitz and Araki. The callousness inscribed by Araki in taking the photograph, reflects to the audience a more cold and documentary approach, which can be inferred as a coping mechanism on Araki’s part to deal with his wife’s death. While the corpse and the funeral rituals of coffin decoration were already undertaken, Araki does not set out to dignify or beautify the process of mourning. The many hands that are laid near his wife’s cold and placid face articulates clearly her being laid to rest – there is no question of this. Furthermore, the narrow, almost claustrophobic scope of the photograph suggests the same – Araki’s response to death is literally by dealing with the reality of the situation, without leaving any space that might reveal the slightest hint of emotion. This is juxtaposed against the personal undertaking of Leibovitz to capture and literally, craft out an image of Sontag that is accorded dignity and respect not unlike the saints in their death.

Death in Time, Memory and Image

Thus, a historical analysis into the subject of death is pertinent here. The subject of death in art can be traced far back into the 16th century, most notably in vanitas art works which originated from the Netherlands. Vanitas itself refers to “vanity”, or otherwise, the transience of life and all worldly matters and pursuits and is commonly associated with the Bible phrase from Ecclesiastes 1:2, “Vanitas vanitatum omnia vanitas”. Such paintings often depicted worldly objects such as jewellery, books, and flowers, symbolizing wealth, knowledge and beauty/life respectively, while juxtaposed against a skull, the momento mori reminder of death and the futility of life. Conversely, post-mortem photography finds its roots far back into the nineteenth and twentieth century, the purpose of which was to dignify the dead and was a means for grieving families to cope. Unlike vanitas paintings which had an underlying commentary of death and life, funerary photography functioned as visual memento mori as well. In these photographs, the corpse would be manipulated and dressed up such that it would resemble slumber or lifelikeness. Later photographs in this period would feature the deceased in a coffin surrounded by flowers, one of the few similarities to vanitas paintings, so as to express the transient nature of life, elucidated by the wilting of flowers beyond the moment captured in the painting or photograph. In modern times, this practice went into extinction, largely because of the changing perception towards mourning practices and death in society. Despite this, post-mortem photography would have found itself in the wider notion of visual memory in mourning processes that persist to this day. Recreating the dead through effigies, statues or other monuments played on the immortality of such physical structures, in direct contrast to the mortality and limitations of the human body. This immortality would then later transcribe itself to the so-called preservation of a life, where the living memory of the person would be retained. As an element of post-mortem photography, and in general, taking the corpse as material, either by refashioning its image, or through relics, would work as reminders and recollections of the body of the person, hence engaging with the living, through the other senses, such as “associated actions, sensations and emotions that are not directly visible within the image.”

The Maybe

1995/2013

by Tilda Swinton

These concepts surrounding death, image and memory is embodied and can be seen in Tilda Swinton’s performance art piece, entitled “The Maybe”. This work includes an installation of an elevated glass box, the description of which reads as “Tilda Swinton. Scottish, born 1960. The Maybe 1995/2013. Living artist, glass, steel, mattress, pillow, linen, water and spectacles.” (Fig. 4). Here, Swinton, as art piece and artist, appears at indefinite timings to sleep in the glass box. Despite no conclusive explanation given for the work, links can be drawn to the same saint-like reverence and glorification of saints that is featured in Christianity. Statues of saints were created for the same aforementioned purpose: with the decay of the body, and the continuity of a soul that would pass into the spiritual world, visual memory took place by using physical constructs to override the transience of the body, and as a symbol for the perpetuity of the soul. The boundaries between sleep and death are also explored in this piece. Embalmers, even to this date, continue to reinstate the deterioration of the corpse, back to its former “prime”, in order to create the illusion of life. Such an image is powerful as it provides a gripping “memory picture” of the deceased for relatives, at the last moments. Swinton also further illustrates this distinction between life and death through the glass box that creates both an alienation of the audience from the art work, while allowing them to also partake in this “cinematic performance”. The audience is allowed to recall, in this visual representation of sleep and death, not only the passing of their own loved ones, but to contemplate on the fine line between life and death, and hence the ephemeral qualities of life. Yet, the glass box also creates both the physical and psychological proximity between audience and subject, thus transcending the boundaries between voyeurism and engaging in the art piece.

For Leibovitz, the “glass box” here is represented through photography itself which articulates both the same distance and invitation to the audience. Curation in itself, as illustrated by Araki, with no semblance of emotional input, alienates the audience through the sense of distance already established – between object and audience. Thus, audience participation may be reduced to voyeurism, whereby what is perceived is framed and objectified. A comparison can be drawn between such voyeurism to animals held in glass enclosures. Visitors on the other side of the glass maintain a sense of superiority over the subjects in the glass enclosures, as there is an observer and object relationship that is created, with the observer being the one with the intellectual capability to link such observations to associated experiences, actions and thoughts. Similarly, in photography, the audience looks at an image as they would at a spectacle.

Voyeurism in Death

The subject of voyeurism can also be analyzed through a different lens, namely forensic photography. Here however, a sense of distance between subject and “audience” is established from the very nature of forensic photography itself which demands “as one of the primary documentation components, systematic, organized visual record of an undisturbed crime scene”. The purposes of forensic photography necessitate the complete detachment of emotion, opinion or other human traits from the subject in order to achieve an objective, even calculated image. Araki’s aforementioned work is reminiscent of this same documentary approach – death becomes a narration of nothing more than itself.

The confluence of art and forensic photography is embodied in Angela Strassheim’s Evidence project. Strassheim, a former forensic photographer, translates her professional skills into the realm of art (almost similar to Leibovitz), whereby her work Evidence, is a collection of photographs taken at 140 homes across the United States that were once homicide crime scenes. Using Bluestar solution, a latent bloodstain reagent, Strassheim exposes the once violent past of the place which now houses new residents that are sometimes unaware of the events that have taken place before. Her black and white images are long exposures, with minimal night light filtering in from obscured windows, each bearing a title that states the murder weapon and details of the events.

Intriguing and quietly eerie, these images reflect forensic photography in that each of the photographs is a documentation of the evidence at a crime scene. Minimalism is evident as the image is stripped away of any unnecessary additions, and the backdrop of the house is dimmed into obscurity – instead, the residual bloodstains are luminous like constellations mapped across a night sky. Yet the audience is well aware of the living space around it that subtly frames an image of human monstrosity. A particular haunting image, “Evidence No. 2, 2009” (Fig. 8) features a splatter of blood glowing across the wall, draped above an unmade bed now occupied by its new inhabitants. Prima facie, the image is aesthetically pleasing; the unmade bed seems vaguely comforting and the bloodstains, juxtaposed against the two light switches hanging down the centre, are incandescent sparks of light. To superimpose the ghost of those tragic moments that infringed upon the boundaries of life and death, and to realize the evidence of which is embedded on the walls and obscured from plain sight, renders the ostensibly innocent over-layer of the wall into something a haunting, all at once more menacing and sinister. In “Evidence, #11, 48×60” (Fig. 7), the surrounding living conditions is explored in greater depth as the bloodstains are now part of the background. Instead, the light from the television set seems to be the focal point. This blending in of the bloodstains is once again, a subtle obscuring of the past tragedy and asserting that continuity of life that perhaps, has also accepted death into its very essence.

Evidence #11, 48×60

2008

by Angela Strassheim

Evidence No. 2

2009

by Angela Strassheim

Hence, death itself is obscured by the image, cleaning/refurbishing and time and Strassheim invokes the continuity of life even after the tragedy and horrors of homicide has come to pass in a place. Like scenes out of film noir, photography leads to the immortalization of something already immortalized – blood leaves a permanent stain even when emotions, humans, and even memory has faded away into oblivion/non-existence. It is a scene of momento mori, where the veneer of homeliness is juxtaposed with the figure of death, looming in the shadows, the inhabitants often unaware of its presence. Unconsciously, vanitas has also become a subconscious commentary hidden in the backdrop of their lives and serves perhaps also, as a timely reminder to the audience about the close proximity of death to their own lives. And it is with this implication that the photographs gaze back, indifferently and unflinchingly at the audience, who are voyeurs by their own right, the voyeurism occurring in what has been left unsaid, in what can be imagined.

In this sense, voyeurism is obscured here as what is presented is not death in itself, but the subtle implications of death. While Sontag’s death does not entail with it the same abhorrent implications, a stark contrast is struck here between Leibovitz’s photograph of death and Strassheim’s pseudo-forensic photographs. By imposing the image of death itself on the audience, Leibovitz is able to subtly steer the audience to view Sontag as how Leibovitz herself regards her, instead of leaving the echoes of death to ring with an audience that might return disturbed or even disgusted. Disregarding the obvious suggestions of violence in Strassheim’s photographs, her series is a twist on vanitas, and the silent insinuations of an imminent death that surrounds people, even in their state of comfort and stagnancy of everyday life. Yet, the obscuring of death camouflaged into the walls in Strassheim is paralleled by Leibovitz who fails to give a title or date to Sontag’s death as part of her larger oeuvre. Instead, the image is placed silently between the pictures of Sontag returning, ill and dying from Seattle, and Leibovitz’s parents and brother. Arguably, Leibovitz’s photograph of Sontag’s death encapsulates to a greater extent, visual memento mori, not for the dead but for the living. It is a photograph very much embedded into the walls of Leibovitz’s personal collection, an intimate reflection and arguably, a means of letting go.

Questionably, David Reiff’s criticism of the photographs as “carnival images of death” holds little truth. Sontag writes in her essay, “On Photography”, that the “…ambiguous relationship [between photographer and photograph] sets up a chronic voyeuristic relation to the world which levels the meaning of all events”. Although a certain degree of voyeurism may be inevitable due to the nature of an exhibition (which implies a certain exhibitionist quality to the artist) especially in capturing images of death, Leibovitz makes attempt to bring this further, and in a way, allows audiences to pay their final respects and contemplate the death of this force of intellectual brilliance. As a corollary, the sense of distance created through photography is also leveled by the invitation for audience participation. The emotional response that Leibovitz articulates in the photograph creates the human link whereby audiences are invited to reciprocate the response. This emotional link is two-pronged. While the audience is asked to participate in Leibovitz’s grief, they are also incited to “kill” Sontag. This mental dying is unlike Araki’s obstinate acceptance, but rather, the visual impact would compel audiences to retain the death of Sontag as pure memory, and not by physical reminders in itself. Photography becomes a metaphor for death, and Sontag’s life and legacy is contained by these images, without being Sontag in itself.

The content of the images also suggest that Leibovitz’s photographs go beyond voyeurism. By creating the photograph in parts, and later piecing it back together again in curved overlaps, Leibovitz attempts to humanize the photography experience as it reflects the reconstruction of Sontag’s unrecognizable, and nearly withered features of her corpse into the concept of Sontag as an individual, as seen through Leibovitz’s eyes. This harks back to the photograph of Sontag at Hedges Lane. By humanizing the dead Sontag, she inevitably immortalizes Sontag into the image of Sontag alive, breathing and lying on a couch. It is the image of Sontag that she chooses to retain. The overlapping of the photograph also delineates itself, into a second set hidden underneath the dominant photograph, suggesting a personal experience of Sontag only known to Leibovitz, purposefully and metaphorically, kept away from the public eye. Perhaps in large part also, while this photograph may have garnered greater celebrity attention for Leibovitz, the publication and capturing could have acted as a form of release for Leibovitz, as a sharing of her life which was dominated by the presence of Sontag. This is further reinforced by the “breathing space” given to Sontag, whereby the photograph does not consist only of her image, but has also taken into account the purview of her surroundings, which gives context and the sense of Sontag resting peacefully.

Hence, taking into account the larger polemics of death photography, and its ethics, Leibovitz successfully transforms the corpse from the demeaned state it resides in, into a dignified process of mourning through photography. The modern day tradition of preserving the sanctity of death is sustained as such, through the medium of photography which is all at once, a public and private affair that is able to distance and compel the audience. Rather than mere documentation or voyeurism, it finds its place in the exhibition and marks a somber moment in the story, where death seems to be pervasive in Leibovitz’s life. For her, this is an act of remembrance and a means of letting go. Hence, rather than carnival, the composure of Sontag in the photograph suggests only a mere slumber – the audience is invited not to gawk at her death, but rather, meditate upon this once-intimidating force of Sontag now laid to peaceful rest.

—

References:

1 San Diego Museum of Art, Working Exhibition Checklist, Available: http://www.tfaoi.com/cm/4cm/4cm526.pdf [Accessed: 1st September].

2 David Rieff, Swimming in a Sea of Death: A Son’s Memoir, (New York: Simon & Shuster, 2008), p. 150.

3 Caitlin McKinney, Leibovitz and Sontag: picturing an ethics of queer domesticity, Shift Queen’s Journal of Visual and Material Culture, Available: http://shiftjournal.org/archives/articles/2010/mckinney.pdf [Accessed: 1st September].

4 San Diego Museum of Art, Working Exhibition Checklist, Available: http://www.tfaoi.com/cm/4cm/4cm526.pdf [Accessed: 1st September].

5 The Economist, Obituary Susan Sontag, Available: http://www.economist.com/node/3535617 [Accessed: 1st October].

6 Elizabeth Hallam, Jenny Hockey and Glennys Howarth, Beyond the Body: Death and Social Identity, (Routledge: London), 1999.

7 Angel McRobbie, While Susan Sontag lay dying, Open Democracy, Available: http://www.opendemocracy.net/people-photography/sontag_3987.jsp [Accessed: 28th September].

8 Blouin Artinfo, Review: Nobuyoshi Araki’s Sentimental Journey, Available: http://encn.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/962502/review-nobuyoshi-arakis-sentimental-journey [Accessed: 2 September].

9 The Burns Archive, The Death and Memorial Collection, Available: http://www.burnsarchive.com/Explore/Historical/Memorial/index.html [Accessed: 2nd October].

10 Elizabeth Hallam, Jenny Hockey, Death, Memory and Material Culture, (Bloomsbury Academic: Michigan), 2001, p. 133.

11 ibid.

12 AnOther, Tilda Swinton’s The Maybe, Available: http://www.anothermag.com/current/view/2664/Tilda_Swintons_The_Maybe [Accessed: 3rd September].

13 Elizabeth Hallam, Jenny Hockey and Glennys Howarth, Beyond the Body: Death and Social Identity, (Routledge: London), 1999.

14 AnOther, Tilda Swinton’s The Maybe, Available: http://www.anothermag.com/current/view/2664/Tilda_Swintons_The_Maybe [Accessed: 3rd September].

15 Lee, Henry C., et. al., Henry Lee’s Crime Scene Handbook, New York: Academic Press, 2001.

16 Women in Photography, Angela Strassheim, Available: http://www.wipnyc.org/blog/angela-strassheim [Accessed: 1st November].

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Cara Takakjian, Book Review, Available: isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic148217.files/TakakjianSontag.htm [Accessed: 4th September].

Leave a Reply