In every Calendar Year, Tembusu College awards prizes for the Best Essay, Best Creative Work and Best Miscellaneous Work to recognise the intellectual achievements of Tembusu students in the University Town College Programme (UTCP). Each category features two winners. This essay by Tan Guan Yu, written for the course Asia Now! The Archaeology of the Future City, was the winner of the Best Essay Prize for the Calendar Year 2022. It is published here in two parts. It is the first of a series of prize-winning essays and other works that Treehouse will be publishing. Treehouse hopes that the publication of these student works will further contribute to the intellectual collective within the college.

INTRODUCTION: SAVING SEMAKAU

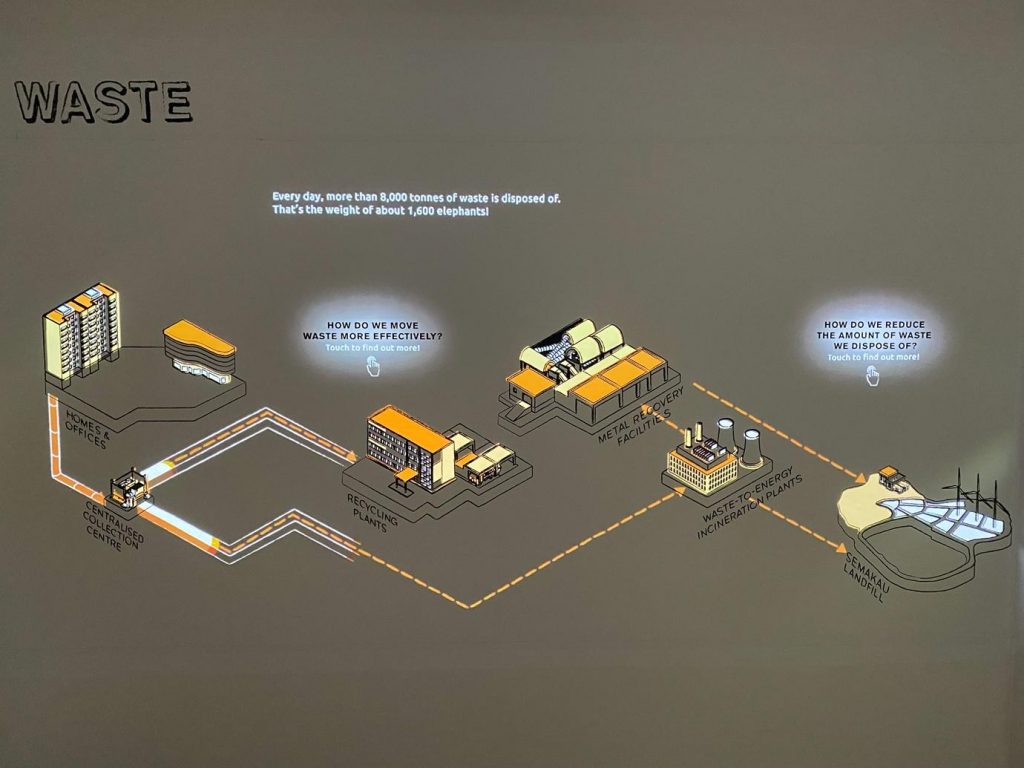

Emphatically, cities are characterized as “entropic blackholes” which relentlessly extract productive capital from the ecosphere before returning it back to nature as waste (Rees and Wackernagel, 1996, p.237). Although Singapore has proudly declared its aspiration to become a Zero Waste Nation, there appears to be a stark gap between the reality and the rhetoric. Grim statistics derived from my visit to the Singapore City Gallery suggest the city-state disposes more than 8,000 tonnes of waste daily, which is equivalent to the weight of about 1,600 elephants! (Figure 1). While Singapore’s only sanitary landfill, Semakau, is specifically created to accommodate the nation’s mounting waste problem, it merely presents itself as a band-aid solution to face off the escalating amounts of municipal waste generated. As the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (2021) cautions, Semakau Landfill will run out of space by 2035. Should land-scarce Singapore fail to defuse this 13-year ‘waste timebomb’ (Hicks, 2019), a second landfill may not be viable, hampering her progress to successfully become a Zero Waste Nation.

SINGAPORE: A NATION OF PLASTIC

While recognising the fact that solid municipal waste management extends beyond plastic waste, a fine-grained analysis of plastic waste is necessary in light of its role as one of Singapore’s largest waste streams. According to the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (2021), the city has generated a whopping 868,000 tonnes of plastic waste in 2020 with only 4% being recycled. Branded as a “necessary evil” (Paine, 2002, p.167), plastic is a ubiquitous material that is used in packaging, disposable ware and single-use grocery bags. Using COVID-19 as the backdrop, Chen and Tan (2021) posit a surge in plastic use because of growing interests in online shopping and its heavy reliance on single-use plastic for packaging. Given the non-biodegradable nature of plastics, the majority of plastic waste heads straight to the incinerators before being disposed of as sludge into Semakau Landfill.

Nonetheless, all is not lost when it comes to plastic waste management in Singapore. In the course of this two-part article, I will explicate how a synergistic multi-stakeholder collaboration in the disposal, processing, and generation of plastic waste can potentially help Singapore make headway in reducing plastic waste and landfill deposits. However, to successfully close the plastics loop, this article then argues for a deeper analysis of the impetus behind our unwavering demand for plastics which can be attributed to cost, convenience and our consumerist lifestyle (3Cs). Last but not least, drawing insights from Taipei’s innovative waste collection system, this article attempts to contribute to scholarship by proposing plastic waste management as a suitable livability-sustainability nexus for consideration in Singapore.

3P PARTNERSHIP IN PLASTIC WASTE MANAGEMENT

As Hee and Dunn (2013) suggest, collaborating across different stakeholder groups can improve development strategies and produce win-win solutions. In the context of plastic waste management, the public sector is largely responsible for heavily investing in sustainable infrastructure to meet the nation’s long-term plastic waste disposal needs. According to the National Environment Agency (2017), the state-of-the-art Integrated Waste Management Facility (IWMF), which is due for completion by 2025, consists of a complex material recovery facility capable of sorting out recyclable plastics due for landfill disposal. Although the IWMF’s recovery technology is still in its infancy, the government projects 250 tonnes per day of recyclable plastics from the National Recycling Programme can be sorted, thereby minimizing landfilling demand.

In partnership with the public sector, commercial firms too are finding their footing in the plastic waste management ecosystem, actively breathing life into recycled plastic, processing trash into treasure. Drawing inspiration from the construction industry, Magorium, a deep-tech start-up in Singapore, seeks to repurpose plastic waste like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles and single-use bags into a key road tarring ingredient to form its novel NEWBitumen mix (Magorium, n.d.). Hinging upon the inherent qualities of plastic as a highly water-proof and flexible material, this award-winning start-up is seeking to create environmentally-friendly roads that have greater durability in the long run (Tang, 2020). By allying with the National Environment Agency, discarded plastic collated by Magorium can ingeniously pave the way for greener roads, instead of just being destined for the fast-shrinking landfill on Semakau island.

Beyond public-private partnerships, Budicâ et al. argue that waste management is a “commitment and a duty of each citizen” (2015, p.13). While local authorities and private businesses can provide the necessary infrastructure and recycling technology to manage waste disposal and processing, a dearth of consciousness (Budicâ et al., 2015) with regard to our massive generation of plastic waste would not help in prolonging Semakau’s landfilling potential. To raise awareness about the excessive dependence on single-use plastics in the community, Plastic-Lite SG is a grassroots volunteer group which has initiated several campaigns like Bring Your Own Bag (BYOB) and Bounce Bags to encourage shoppers to bring their own reusable bags and spread the word about the negative impacts of single-use plastic bags (Plastic Lite SG, n.d.). Instead of being fashioned with a complicated board of management and “rubber stamp advisory committees” (Arnstein, 1969, p. 218), Plastic-Lite SG is run by environmental advocates who are determined to curtail and ‘refuse’ unnecessary plastic waste. Via a multi-stakeholder collaboration to address issues arising from the disposal, processing and generation of plastic waste, there is a call for optimism in reducing plastic waste and landfilling demands.

TACKLING THE ROOTS OF GROWING PLASTIC WASTE

However, to successfully close our plastics loop, Singapore cannot simply rest on her laurels and depend solely on a multi-stakeholder collaboration. Based on the inaugural OCBC Climate Index (2021), although 81% of Singaporeans are cognizant of the fact that plastic bags take an extremely long time to naturally degrade, only a mere 22% of the population has been actively shopping with reusable bags. To steer Singapore towards a Zero Waste Nation, adopting the right consumption practices must be commensurate with the level of awareness. Drawing on personal experiences, nipping the problem of growing plastic waste generation in the bud necessitates a close scrutiny on the barriers which disincentivise individuals to reduce plastic consumption.

Firstly, cost presents itself as a huge barrier to plastic-free consumption. According to Wiefek et al. (2021), higher prices of groceries packaged in glass compared to groceries in plastic containers deter price-sensitive consumers from moving away from plastic-packaged goods. In the same vein, for a financially strapped consumer like myself, the most pragmatic and utilitarian choice would be to opt for the cheaper alternative that is packaged in plastic. In line with Schneider-Mayerson’s (2020) critical assessment of Singapore as a “practical nation” (p.178) operating within a global regime of capitalism, it is not surprising to witness how many Singaporeans would emulate my purchasing decisions and share similar sentiments toward consuming plastic packaged products.

Secondly, Wiefek et al. (2021) argue that the pervasive culture of convenience presents a significant impetus to the continued use of plastics. Lauding single-use plastic bags to be light-weight, easily portable and highly durable, Wiefek et al. (2021) posit strong resistance amongst consumers to refrain from the habit of using plastic bags when purchasing groceries in zero-packaging stores. Case in point, while I am deeply impressed with the way the organic grocery store Scoop Wholefoods Singapore seeks to promote environmentally-responsible shopping by eradicating plastic bags with paper bag substitutions, heavy items often result in the paper bag buckling under its weight. As plastic bags are more durable, consumers like myself find it extremely challenging to refrain from indulging in this “necessary evil” (Paine, 2002, p.167). Additionally, the OCBC Climate Index (2021) suggests many individuals find it a ‘hassle’ to constantly bring along reusable shopping bags. The ubiquitous presence of single-use plastic bags in many large supermarkets has further given convenience a booster, limiting opportunities for a cultural overhaul.

Thirdly, Wiefek et al. (2021, p.3) suggest our consumerist lifestyles remain a key factor when explaining why plastic consumption is so “deeply-rooted” in many societies. As Goh Chok Tong once remarked in his 1996 National Day Rally speech, “life for Singaporeans is not complete without shopping!” (cited in Schneider-Mayerson, 2020, p.176). As Singaporeans fix our gaze on intense consumerism through shopping and purchasing of material goods to create our self-validated ‘good life’, we unwittingly manifest into a “living oil” (Schneider-Mayerson, 2020, p.177), inundating our bodies with plastics, polymers, and other plastic by-products, which eventually undergo the ‘make-use-dispose’ linear process and become landfill deposits. Since material wealth is a symbolic status for most Singaporeans, we gradually become “inured” (Schneider-Mayerson, 2020, p.175) to the consequences of plastic waste on our sole landfill. This desensitization inevitably creates many “attitude-behaviour-gaps” (Wiefek et al., 2020, p.2) and increases inertia for Singaporeans to curtail their plastic consumption.

CONCLUSION: BEYOND SKIN DEEP

While I acknowledge the fact that tackling these root causes, which are accountable for the ever-growing amount of plastic waste, is an uphill task, the current Business-As-Usual mode cannot continue. Beyond fervently sourcing for ways to prolong the use of our offshore sanitary landfill, which has been stuffed by our “throwaway culture of capitalism” (Schneider-Mayerson, 2020, p.101), a “lifestyle against accumulation” (Meissner, 2019, p.185) can perhaps be something in which consumers can consider. Purchasing quality over quantity and upcycling plastic bottles and packaging are low-hanging fruits Singaporeans can pick to navigate the contemporary problems arising from “a world of too much” (Meissner, 2019, p.187).

Despite achieving some tenable level of success in the management of plastic waste, deeper shifts need to happen. While the Singapore government continues to actively push forth its Zero Waste Master Plan, the suite of environmental burdens induced by plastic waste cannot be shouldered solely by the administration. Delving into the messy but critical realities of people’s engagement with plastic, cost, convenience, and consumerism have opened new windows for us to rethink our relationship with this ‘gentle killer’. In the next segment, we will take a hiatus from the Singapore context to understand how a former economic tiger of Asia has transformed herself from a garbage island to a recycling champion. Using a combination of hard enforcement measures and soft endearing music, Taiwan has successfully remade herself from a garbage island to a world-class recycling champion. Can the Taiwanese way of managing plastic waste be a picture of Singapore’s future?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Budicâ, I., Busu, O.V., Dumitrue, A., Purcaru, M-L. (2015). Waste Management as Commitment and Duty of Citizens. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 11(1), 7–16.

Chen, Z., & Tan, A. (2021). Exploring The Circular Supply Chain To Reduce Plastic Waste In Singapore. LogForum, 17(2), 271–286.

Consumer Plastic and Plastic Resource Ecosystem in Singapore. (2018). Singapore Environmental Council. https://sec.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/DT_PlasticResourceResearch_28Aug2018-FINAL_with-Addendum-19.pdf

Hee, L., & Dunn., S. (2013). 10 Principles for Liveable High-Density Cities. Urban Solutions, 2, 52–59.

Hian, T.H. (2021). The Singapore Economy: Dynamism and Inclusion (1st ed.). Routledge.

Hicks, R. (2019). How will Singapore defuse a 16-year waste timebomb? Eco-Business. https://www.eco-business.com/news/how-will-singapore-defuse-a-16-year-waste-timebomb/

Huff, W. G. (1999). Turning the Corner in Singapore’s Developmental State? Asian Survey, 39(2), 214–242. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645453

Magorium. (n.d.). Sustainable Solutions. https://www.mgrium.com/

Meissner, M. (2019). Against accumulation: lifestyle minimalism, de-growth and the present post-ecological condition. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12(3), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2019.1570962

Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (2021). Launch of the Plastics Recycling Association of Singapore – Ms Grace Fu. https://www.mse.gov.sg/resource-room/category/2021-08-17-speech-at-the-launch-of-pras/

National Environment Agency. (2017). Integrated Waste Management Facility. https://www.nea.gov.sg/docs/default-source/resource/iwmf.pdf

Ngo, H. (2020). How getting rid of dustbins helped Taiwan clean up its cities. BBC Future. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200526-how-taipei-became-an-unusually-clean-city

OCBC Climate Index. (2021). The Inaugural OCBC Climate Index. https://www.ocbc.com/iwov-resources/sg/ocbc/gbc/pdf/sustainability/climate-index/media-briefing.pdf

Paine, F. (2002). Packaging reminiscences: some thoughts on controversial matters. Packaging Technology and Science, 15(4), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/pts.593

Plastic Lite SG. (n.d.). Mindless consumerism. http://plasticlite.sg/

Rees, W., & Wackernagel, M. (1996). Urban ecological footprints: Why cities cannot be sustainable—And why they are a key to sustainability. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 16(4–6), 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-9255(96)00022-4

Schneider-Mayerson, M. (2020). Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene. Adfo Books.

Sung, H. C., Sheu, Y. S., Yang, B. Y., & Ko, C. H. (2020). Municipal Solid Waste and Utility Consumption in Taiwan. Sustainability, 12(8), 3425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083425

Tang, S.K. (2021). This Singapore start-up hopes to make roads with plastic waste. CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/climatechange/start-up-make-roads-with-plastic-waste-singapore-1340136

Wiefek, J., Steinhorst, J., & Beyerl, K. (2021). Personal and structural factors that influence individual plastic packaging consumption—Results from focus group discussions with German consumers. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 3, 100022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clrc.2021.100022

Cover and Banner Image by Natasha Kasim on Unsplash