Introduction

As with all things, it started off innocuously. Stairs felt harder to climb. Trousers that previously were loose now are laughably snug. Sluggishness began creeping in. Of course, I tried attributing these to other causes – the generalized lethargy came from the demands of academic life, the trousers shrank in the dryers, and of course the stairs were harder to climb since we were wearing flip-flops all the time. However, hard as I tried, I could not run away (probably because I don’t run) from the fact that Freshman 15 was hitting, and that it was hitting particularly hard.

The term “Freshman Fifteen” may sound like a marketing gimmick, but weight gain during university years is a commonly acknowledged phenomenon. Olga Khazan at The Atlantic attributes its first mass media portrayal to Seventeen magazine, but also points to a much earlier mention of the Freshman 10 in a 1981 New York Times article. From the almost off-handed way the article’s authors described “the 10 pounds many freshmen gain in their first weeks here [at Yale]”, it seems as if gaining weight in university was already a well-established fact of life. The term skyrocketed in the late 1990s and early 2000s in both university and general newspapers, eventually integrating itself into parlance on campuses around the world.

Gropper and colleagues showed a significant majority of first-year undergraduate students gaining weight, with an average increase of 6 pounds (2.7kg) and 4.4% body fat amongst gainers. This phenomenon also seems transcontinental in nature, being observed in places like England and China. Most pertinent for us Tembusians, it seems that Freshman 15 is exacerbated by residential living. Zella-Varb and Elgar found in their 2010 survey of female students, that those living on campus gained on average twice as much as their non-residential cohorts. What could it be that was causing this? Could residential programmes be unwittingly inculcating in their members some form of epicurean hedonism? Or was some other mechanism at play? Could it be that Tembusu College is an obesogenic environment?

Obesogeneity

Lake and Townshend view the physical space in two separate layers, via its ability to promote active lifestyles and the food practices that it creates. Without delving into the deep nuances, debates, and controversies surrounding weight loss and dietary science, this analysis can be thought to be underpinned by a simple equation: “calories in, calories out”. Calories in is governed by how much we eat and drink, while calories out is a combination of physical activity and our metabolic rate. Going back to Lake and Townshend, the obesogeneity of an environment is highly determined by how easy it is for us to eat calorically dense diets (via food environments and the practices they foster), and how difficult it is for us to be physically active.

Figure 1. Food environments are shaped by spatial, political, economic, and sociocultural factors the guide our relationships with food. Photo by Daria Voljova on Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/BMnX7L9G5xc

Structurally, the former is governed by access and price; if calorically dense food (often high in sugars and fats) is cheaper and more readily available in a certain place, then the people who live near these places are more likely to consume diets that comprise more of these foods. For instance, if we live in a neighbourhood surrounded by fast food joints with few supermarkets and healthy food options within walkable distance, then it is far more likely that we default to these fast-food options rather than literally go the extra mile in search of a healthier lunch. Life is complicated enough as it is. Similarly, if it is inconvenient or unsafe for us to exercise close to our workplaces or homes, we would be less physically active.

Even in environments with a good mix of food options, social factors also have a role in shaping our dietary and exercise habits. Being assigned a physically active roommate for instance is shown to positively impact our own exercise habits. Being surrounded by peers who constantly order supper would no doubt incentivize our supper consumption habits as well.

Tembusu College as Obesogenic?

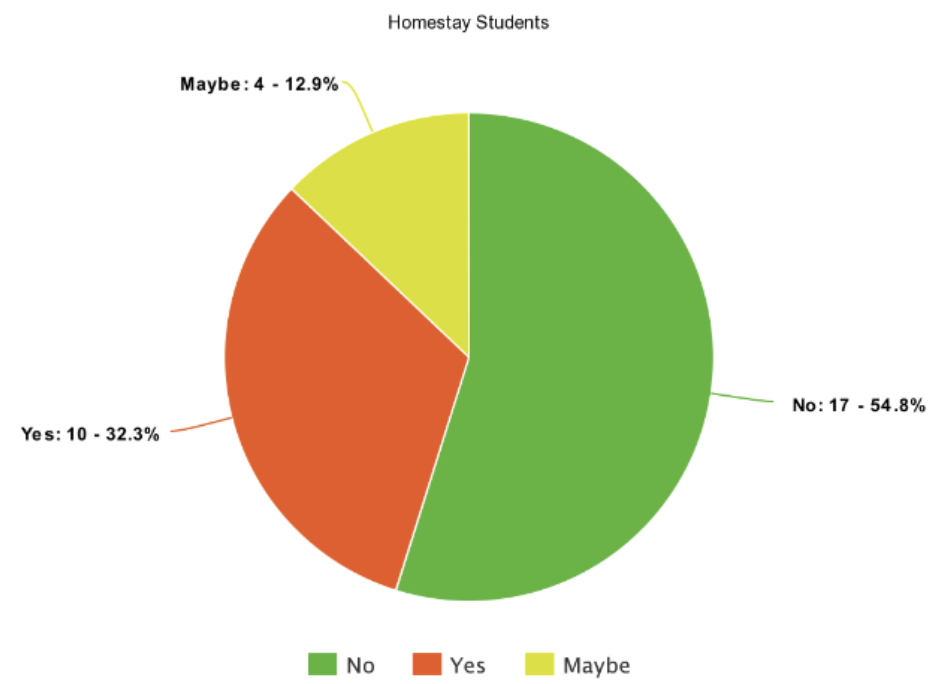

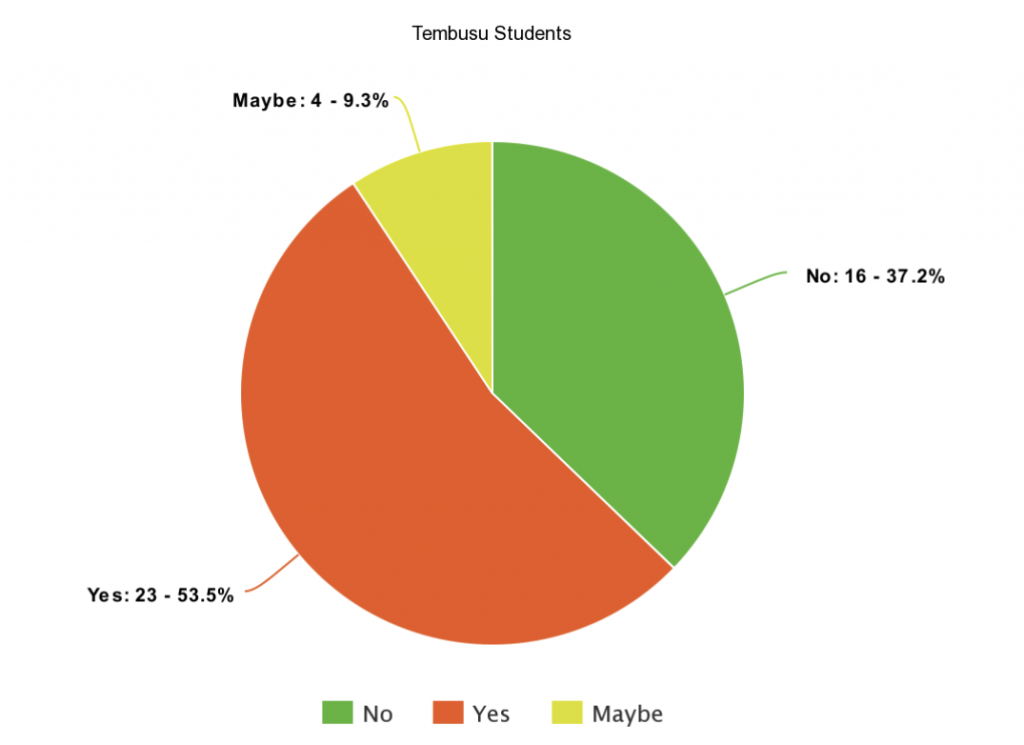

What then can we say about Tembusu College? If Freshman Fifteen is so commonly bandied about both as an observation and a joke, what does this say about the environment which we spend half our university lives in? Last semester, a group of Tembusians (comprising Edward, Kai Qing, Zhan Wei and myself) decided to pursue this phenomenon a little deeper for our Biomedicine and Singapore Society module (UTS2101). The main object of our research was this: whether there was an appreciable difference between perceptions of unhealthy weight gain between Tembusians (Figure 2) and the general non-residential NUS population (Figure 3).

While the difference between Tembusians and NUS Students studying from home was too small to scientifically prove that staying in Tembusu made Freshman 15 worse (our p-value, or the likelihood that the results could have occurred as they did without a stay in Tembusu actually being obesogenic, was 0.193) we decided to probe further.

Figure 2. Pie chart of self-perceptions of weight gain amongst 31 non-residential NUS students

Figure 3. Pie chart of self-perceptions of weight gain amongst 43 Tembusians

Diets

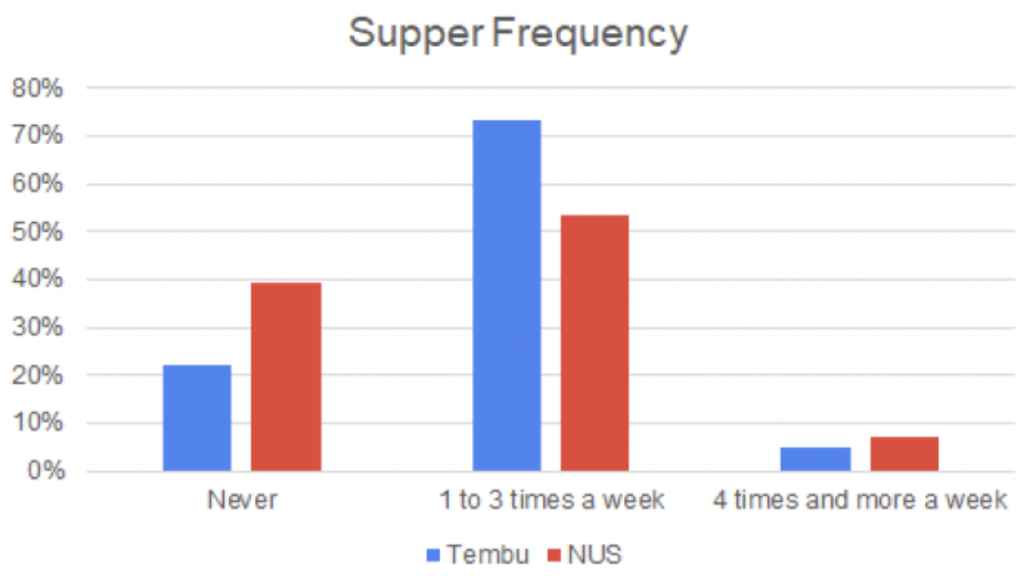

While the obesogeneity of diets is affected by many things, two of the most impactful are supper culture and the scale of calorically dense food options in University Town (UTown). We also decided to look further into this. Given the popularity of supper culture and late nights (resulting in hunger pangs), Tembusu students are more likely to regularly indulge in supper than NUS students studying from home, with more than 70% of Tembusu students eating supper 1 to 3 times a week, versus 50% for homestay students (see Figure 4). This is reinforced by the sheer prevalence of unhealthy food options in and around UTown. Our site observations have indicated that vendors like Supersnacks and FairPrice often load up in their processed snack options, leaving little in the way of nutritionally dense foods.

What if we grow weary of the unhealthy food present in Utown? Enterprising students have even coded Telegram bots to facilitate mass orders (often at the house level) from vendors at “Supper Stretch”. More recently, food delivery platforms and roving food vans have appeared on the scene, providing even more in the form of choice and convenience.

Figure 4. Supper frequency of Tembusu versus general homestay NUS student

What’s perhaps slightly concerning is that for so many of us in Tembusu (or even in the wider campus circles), supper culture has become an integral part of our lives and identities. Jios (invitations) are done at alarming regularity, after every late-night house event, interest group session, or even as a matter of course. It even became a matter of pride last semester, as the entire Tembusu came together during Arts Week finale to spend more than a thousand dollars on butter chicken, naan, and cheese fries.

Exercise

Tembusians also seem to get less exercise than the home-based NUS population, but it is not for want of trying. In our survey, Tembusians who “Never” exercised during the week outnumbered the NUS population three to one (22% versus 7%). This was strangely incongruent with the sheer number of sports Interest Groups, as well as the proximity to running tracks, gyms, and sheltered exercise areas around Tembusu and UTown.

While the exercise infrastructure is there, it is perhaps due to the strictness (both in regulations and enforcement) of past Safe Management Measures (SMMs) that made exercise more prohibitive. Capacity limits especially meant that only a meagre group of students were able to participate. The need to sign up and turn up added yet another barrier to entry – for instance, I kept putting off going for tBoxing simply because I did not want to commit to registering my attendance days beforehand. Was I (and my poor sense of time management) really deserving of the spot in the MPH that someone else wanted and could have done so much better with? Perhaps I would have exercised a lot more with my friends had spur-of-the-moment participation been possible in an era without SMMs and capacity limits.

A Note About Reductionism

Discourse surrounding weight and diet has for the past few decades been controversial and loaded. Debates continue to rage on the importance of various types of fats, the health benefits (or even necessity) of vital macronutrients like carbohydrates. With the science surrounding diet already difficult, questions around fatness and the causality of fatness tend to be even more complicated. Body type acceptance has been shaped not so much by science as by psychological and social considerations, differentiated by gender, ethnicity, and media trends. Discussion of the relative ‘healthiness’ of foods is also shaded by elements of ethnicity and class – a salad drenched in sauce may have similar (or “worse”) nutritional profile to a curry, but to many the latter is always seen as better than the other.

For us, the issue was more of an epidemiological one more than anything, where observable population-level changes often demonstrate social causes at play. The causal relationship between environmental weight gain and negative health outcomes may well be a spurious correlation, but even the factors that relate to both, like comfort eating and decreased exercise may indicate other negative effects and causes that are worth looking at. I think it would be better to address these environmental and lifestyle changes than to not do anything about it. Besides, the opportunity cost to eating more vegetables and whole foods (provided we can afford them) and being more physically active are vanishingly low.

A Way Forward?

Now that we are moving out of the shadow cast by the COVID-19 pandemic, we can begin to think of how to utilize this newfound freedom to render our environment a slightly less obesogenic one. Realistically, little can be done about the physical prevalence of processed snacks in and around UTown. We will remain a food swamp, unless the community can come together and work with authorities in Utown and the individual vendors to sell a better balance of foods. Even that takes months or years to achieve. What I believe can change however, are the choices we make.

Seniors spoke of a time when the food court at the Stephen Riady Centre was open till the wee hours of the night, selling noodles. Perhaps instead of the burgers and fries at Super Snacks, we can instead go to 24-hour eateries at Clementi for more vegetable-laden options. Instead of the limited fare at the FairPrice, we could go to the 24-hour supermarkets in Casa Clementi and the MRT station. With the return of face-to-face classes, perhaps we could buy a balanced takeaway sandwich instead of something oilier and more caloric. Maybe we could cut down on the number of regularly scheduled supper jios and save it up for when it properly counts. Perhaps even break the old record. After all, the cumulative effects of regular consumption are more harmful than sporadic indulgence.

These changes are for sure difficult, but I believe it is feasible with the right social mechanisms in place. Perhaps exercise jios can replace (?) supper jios (unlikely, but my old floor managed it a few times), or field trips to get groceries at supermarkets. Increased pax limits also mean more chances to join physically active IGs. Maybe instead of looking at registering on telegram bots as a chore, we can view it as enforced self-care, a challenge to think and do something other than our most pressing deadlines.

Ultimately, the environment that we live in shapes our behaviour, but we must remember that we can shape it as well. As we move into the summer months, let us try to build up newer, healthier habits to tide us into the new academic year.

Feature Image from jztna from Unsplash. Header Image from Emmy Smith from Unsplash.

About the author:

Voon is a proud third-year Tembusu alumnus from FASS who will one day get past his mathematical trauma.

Bibliography

Brown, Cecelia. ‘The Information Trail of the “Freshman 15”—a Systematic Review of a Health Myth within the Research and Popular Literature’. Health Information and Libraries Journal 25, no. 1 (March 2008): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00762.x.

Gropper, Sareen S., Karla P. Simmons, Alisha Gaines, Kelly Drawdy, Desiree Saunders, Pamela Ulrich, and Lenda Jo Connell. ‘The Freshman 15—A Closer Look’. Journal of American College Health 58, no. 3 (30 November 2009): 223–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480903295334.

Lake, Amelia, and Tim Townshend. ‘Obesogenic Environments: Exploring the Built and Food Environments’. Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 126, no. 6 (November 2006): 262–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424006070487.

Khazan, Olga. ‘The Origin of the “Freshman 15” Myth’. The Atlantic, 5 September 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/the-freshman-15-is-a-myth/379587/.

Tan, Shin Bin, and Mariana Arcaya. ‘Where We Eat Is Who We Are: A Survey of Food-Related Travel Patterns to Singapore’s Hawker Centers, Food Courts and Coffee Shops’. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 17, no. 1 (20 October 2020): 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01031-5.

Vadeboncoeur, Claudia, Charlie Foster, and Nick Townsend. ‘Freshman 15 in England: A Longitudinal Evaluation of First Year University Student’s Weight Change’. BMC Obesity 3, no. 1 (December 2016): 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-016-0125-1.

Vella-Zarb, Rachel A, and Frank J Elgar. ‘Predicting the “Freshman 15”: Environmental and Psychological Predictors of Weight Gain in First-Year University Students’. Health Education Journal 69, no. 3 (September 2010): 321–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896910369416.

Wald, Matthew L. ‘JODIE FOSTER SEEKS “NORMAL LIFE” AT YALE’. The New York Times, 5 April 1981, sec. New York. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/05/nyregion/jodie-foster-seeks-normal-life-at-yale.html.

Xu, Xianglong, Yang Pu, Manoj Sharma, Yunshuang Rao, Yilin Cai, and Yong Zhao. ‘Predicting Physical Activity and Healthy Nutrition Behaviors Using Social Cognitive Theory: Cross-Sectional Survey among Undergraduate Students in Chongqing, China’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 11 (November 2017): 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111346.

Yakusheva, Olga, Kandice Kapinos, and Marianne Weiss. ‘Peer Effects and the Freshman 15: Evidence from a Natural Experiment’. Economics & Human Biology 9, no. 2 (March 2011): 119–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2010.12.002.