The shipment arrived on a weekday morning. Seven hundred powerbanks, stacked in brown cardboard cartons, taped at the seams, labelled in bold black print.

Seven hundred powerbanks. They were meant to be corporate gifts, but before they could be given away, someone had to check them.

That someone was me.

My task was simple on paper: quality control. Inspect the powerbanks, ensure their packaging was presentable, and sort the ones with dents or tears aside. Four hours later, hunched over a veritable mountain of cardboard and plastic, I realised something about the work – about sorting as a whole. The metaphors were everywhere, and they felt uncomfortably familiar.

Box Size Matters

The cartons came in two forms. One type carried twenty-five units: Neat, compact and cushioned with more than enough space. The other type carried a hundred: cramped so tightly that the boxes bulged, their edges pressed into one another, their corners frayed.

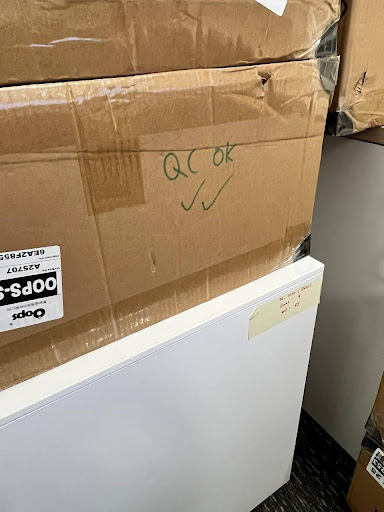

The type of box capable of carrying 100x units. Note the bulging sides. I would like to highlight the edge protectors (black, made of hard plastic, present on all the corners). They were absolutely useless in preventing damage.

The result was obvious. The big boxes produced the most casualties. Dents. Tears. Plastic warped into unfamiliar shapes. The powerbanks inside were the same. But their journey made all the difference.

It is the same in classrooms. Put a child in a smaller group, and there is space to breathe, to be seen. Put a hundred children together, and even the strongest start to buckle. The problem may not be the child, but the box. There is a reason why class size and student-teacher ratio are two key indicators closely monitored by policy makers. These factors influence both the quality of education and the ability of systems to meet the needs of students.

Indeed, we often mistake damage for deficiency. But sometimes, it may just be compression.

The Act of Sorting

My first task was to lift each powerbank out, examine its packaging, and assign it to one of two piles: “good quality” or “reject.”

But a few units in, a problem occurred to me, that the act of handling itself caused harm. The lifting, the turning, the putting back down – an inadvertently tighter grip on my part, or an accidental bump against my desk, and boxes that had looked pristine at first emerged with faint creases.

The very process of assessment created damage.

I thought back to my first years in an “elite” IP secondary school. When I failed my Sec 2 exams, I was streamed into the O-level track, what we called the ‘Structured Integrated Programme’, or SIP for short. The process was supposed to be neutral and based purely on results. However, the act of streaming itself left marks: humiliation, a sudden drop in opportunities, a quiet shift in how others saw me.

The day I received the notice, I remember holding the slip of paper, feeling like I had been pulled out of one pile and set aside. The message was clear: no longer “good quality.”

Sorting is never neutral. It always leaves scars.

Second Chances, First Biases

When the piles were done, I decided to do a second round of checking. Maybe I had been too harsh. Maybe some “rejects” could be rescued. I didn’t even know why I had thought of them as rejects in the first place.

But I quickly realised my bias. The good-quality packages received the benefit of the doubt. A tiny crease could be forgiven. The rejects, however, faced harsher judgment. Even when they looked fine, I found flaws.

The first decision shaped the second. My eyes wanted to confirm what my hands had already declared.

In SIP, I knew that bias firsthand. My former classmates soared in the IP, their paths cushioned with enrichment programmes and dialogues with SAF generals and tech CEOs. My SIP classmates were treated as if failure was expected. Even when we rallied, scoring the rare academic award or CCA achievement, the shadow of that first label clung to us. We clawed back our place, but it was never the same.

When it came time to repack, instinct kicked in. The good packages went into the sturdiest cartons, cushioned with extra care. The rejects were stacked roughly, exposed to further wear.

That was my JC life in miniature. I was lucky enough to enter my JC’s Humanities Programme (HP). Those in the HP – the “Oxbridge feeder” track, got the best facilities, the best teachers, the most protection. I was lucky enough to be there, but it was never lost on me that many others, perhaps just as capable, were denied the same cushioning.

In a way, the education system’s sorting isn’t random; it’s architectural. It allocates students into roles that sustain the machinery of society. A few are trained to lead, the rest to follow. We call this efficiency, but it’s also hierarchy by design. Each student becomes a different kind of battery: some powering policy, others keeping the lights on quietly in the background.

But who, after all, decides what counts as “reject”?

Meritocracy, after all, was built on a promise: that ability and effort would outweigh privilege and birth. Indeed, this is a noble ideal. But what if the problem lies not in the sorting itself, but in the systems we use to measure merit? Over time, merit has increasingly grown to mean the ability to perform in polished ways: to look the part, speak the part and fit neatly into what the system recognises as excellence. The result is not fairness, but filtration: a process that rewards those already familiar with the rules.

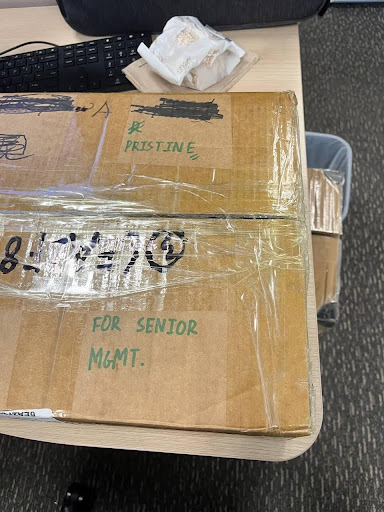

I was asked to pick out the most flawless units to issue to senior management. This was how I labelled them. The analogy writes itself. (Text: PRISTINE. FOR SENIOR MGMT.)

Who Decides What Counts as “Reject”?

The troubling part: none of the powerbanks were broken. Every single powerbank worked. The batteries charged just fine. The only problem was cosmetic. They were downgraded not for their function, but their looks. The label “reject” referred only to their packaging.

Education works the same way. I watched classmates with stellar portfolios stride confidently into government scholarships. On the other hand, I saw classmates that often felt inferior not because they lacked ability, but because they lacked polish. Polish such as how to speak with a ‘proper accent’ or how to hold your cutlery during a scholarship tea session.

Singapore prides itself on pragmatic sorting: each student, placed where they can best “contribute.” Meritocracy presents itself as fair because everyone, in theory, is sorted by effort. But fairness assumes equality at the start line. In reality, we are sorted not from the same place, but from different kinds of packaging: some arrive already bubble-wrapped in resources, connections, and polish, while others do not.

The system calls this fair competition, but it often only measures how well each box survives compression.

The battery inside was still working. But that wasn’t always what mattered.

The box on the left was (obviously) part of the reject pile. The box on the right was pristine. And yet, I managed to lose track of which powerbank belonged to which box. They were both identical.

The Final Question

By the end of the afternoon, my cubicle was tidy. Good pile, reject pile. Order restored.

It looked efficient, rational and necessary.

I thought of myself sitting in interviews, listening to JC classmates talk about internships at Fortune 500 firms or working with MPs. I felt small, not because I lacked ability, but because my polish was different. My personal “packaging” was nights spent giving tuition after school and weekends juggling part-time jobs. Not summer school at Cambridge or internships at the Prime Minister’s Office.

I don’t think meritocracy is inherently broken. But over the years, it has been stretched thin. Meritocracy’s promise of fairness has been warped by how we define “merit.” True meritocracy would look beyond polish and pedigree, beyond who speaks well in interviews. It would value persistence, empathy, and the quiet labour that doesn’t make headlines.

True meritocracy would look beyond sheen and circumstance. It would recognise the quiet endurance of students who work double shifts, who make do with less, who keep trying anyway. It would see worth not as measurable output, but as the effort to keep going.

When I think back to the powerbanks now, I remember not their boxes’ scratches or dents, but how they still turned on: literally doing what they were meant to do. Maybe that’s all any of us are trying to do: to keep going, even when the box around us is less than perfect.

Of course, these were only plastic boxes. A new shipment was already on its way. The rejects would be repacked and restored. But students are not plastic boxes. They do not arrive in replacement shipments. Their time cannot be reordered, and their futures cannot be paused until better packaging arrives.

Aren’t they?

About the Author

Dex is a Y2 Global Studies and Political Science student who often likes to yap about anything and nothing in particular. He assures everyone that, really, he is trying to participate in more IGs, but simply lacks the time.